Modern Hawaiian warriors revive the ancient fighting art of lua

By Naomi Sodetani, photos by Dana Edmunds

| |

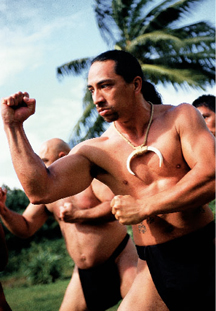

"Ha, he, hu! Ha, he, hu! Ha, he, hu!" The room echoes with the guttural chorus of their breathing, each breath inhaled and expelled in an explosive mantra. Their powerful, fluid movements evoke a curious mix of disciplines: martial drills, hula, Asian combat moves. They lunge forward and back, dodge from side to side, then whirl and pivot in unison, as arm strikes aim for an invisible opponent's eyes, then throat. Their deep breathing and the vigorous stamping of their feet on the floor produce a hypnotic rhythm, punctuated by shouted chants.

A muscular man hovers nearby, eyeing their every gesture, firmly exhorting: "Don't look down; that weakens you." On his command, they assume the boxer-like posture of the tiki: legs and elbows deeply bent, fists clenched, eyes blazing. They are ready to rumble, glistening with sweat and purpose. With each ai, or move, this handful of modern warriors are reclaiming a cultural legacy: the ancient Hawaiian fighting art of lua.

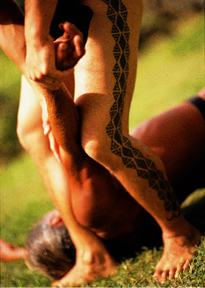

In olden times, lua warriors were the chief's elite commandos. Secretly, in the dark of night, they practiced rigorous hand-to-hand combat in sacred compounds dedicated to the war god Ku. On the battlefield, they killed efficiently, with calculated blows. Precise nerve strikes paralyzed the enemy, followed by a methodical process of "bundling up" the opponent by dislocating his joints, breaking every major bone in his body, and, finally, snapping his back. According to legend, a select few could kill with a mere word or touch, driving the life from their opponents before they hit the ground.Warriors underwent tests of skill and concentration, such as holding their arms out 90 degrees, as a person walked upon each arm. They learned balance by kneeling on gourds without breaking them. To cultivate agility, they practiced weaving their bodies swiftly through a ladder of tautly strung cords.

But in their daily regimen, warriors trained not just to develop their prowess in battle, but also their mental and spiritual sides, through practices associated with the moon goddess Hina, the yielding, feminine counterpart to Ku's aggressive male principle. "Warriors were not brutes," says modern-day lua teacher Jerry Walker. "They also composed poetry, danced, surfed and excelled in sports and games."

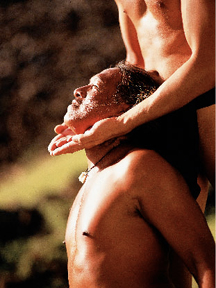

Pragmatically, lua warriors were also master healers adept in practices developed to restore the wounded. Lua master Mitch Eli says that warriors practiced lomilomi massage to aid good circulation and alleviate muscle spasms and sprains, the art of laau lapaau (herbal healing) to make poultices and potions, and even a technique of mending bones, called haihai iwi, an ancient Hawaiian cousin to modern chiropractic care.

"The key lesson is to become balanced and flexible," says teacher Richard Paglinawan, a serious, soft-spoken man in his sixties. "There is a time to be hard like Ku, and a time to be Hina, soft. Lua teaches us to hoomau (persevere), to flow with life, not fight it."

| |

But one olohe lua (lua master) survived: Charles Kenn. A Hawaiian-Japanese-German kahuna (expert or priest) born in 1907, Kenn was also a social historian, professor and author who was highly accomplished in a variety of martial arts, including lua. Although he shied away from public recognition, Kenn was honored in 1976 as a state "living treasure" for his pioneering work documenting Hawaiian language, culture and spiritual traditions long before the present-day Hawaiian renaissance took hold.

Kenn learned lua from several teachersb including two who had trained at a royal lua school established by King Kalakaua in the late 1800s. He also studied with renowned sensei Seishiro "Henry" Okazaki, who had learned lua ai from a Hawaiian practitioner after World War I and incorporated them into his Danzan-Ryu style of jujitsu.

Thirty years ago, Kenn agreed to teach the esoteric art to five dedicated students: Richard Paglinawan, Jerry Walker, Mitchell and Dennis Eli, and Moses Kalauokalani. Today, the five head two lua pa (a figurative term for school), Pa Kui-a-Lua and Pa Kui-a-Holob, that are carrying on and spreading the ancient tradition.

Growing up, Jerry Walker and his college chum Mitch Eli had heard stories about lua. Avid martial artists who were well-versed between them in jujitsu, tai chi, aikido, kung fu and karate, both were eager to learn lua, but they could never find anyone who practiced or taught it. The secrecy that fueled lua's mystique as a potent "dark art" had also erased the path to learn it.

| |

In 1974, Walker tracked Kenn down. At first, the scholar agreed only to teach general Hawaiiana, and only to those who could prove they were descended from alii, or royalty. (Because in ancient times royal blood was believed to contain more mana, or spiritual energy, Walker explains, only the alii underwent intensive training as lua warriors. But during war, makaainana, or commoners, were often drafted into service and taught the basics of lua.)

A dozen students, including Mitch's brother Dennis and acquaintances Paglinawan and Kalauokalani, began meeting regularly with Kenn. He eventually taught them a few lua ai, but imposed a strict kapu on the students talking about their lua practice outside the lessons. When their ranks finally thinned with the rigor and tedium of practice until only five were left, Kenn said, "OK, now we can begin."

For five years, the group met once a week at a house in the Hawaiian neighborhood of Papakolea. "We'd work out from 6 to 10 p.m., then go in and have coffee and pastry," Walker recalls. Then Kenn would lecture on lua, often past midnight, but "time would fly."

In 1978, Kenn anointed his five students as oloh (literally "hairless," because the bodies of master warriors used to be plucked bare and oiled to prevent an enemy from obtaining a sure grip). In exchange, he required of them a promise that they would teach lua only to Hawaiians, to help restore their connection with their culture.

| |

In 1991, Pa Kui-a-Lua member Lynette Paglinawan, Richard's wife, who was then executive director of the Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Project, organized a program to research and perpetuate the dying tradition. The fruits of that effort, funded by the Bishop Museum and the National Park Service, will be published this year in the first comprehensive sourcebook on the subject: Lua: The Hawaiian Martial Art.

Bishop Museum Collection Manager Betty Kam admits that initially the museum, used to tamer academic fare, was "nervous" about "publishing these moves that could really hurt a person. People would say, "Is this too vicious to come out?" But eventually the museum decided the research belonged in the public domain, not in its archives gathering dust. "We hope it will help the broader community understand lua's important role in Hawaiian society, how it connected to many elements of daily life," Kam says. "Lua supports everything we know about Hawaiian culture and shows us how things work in grand interplay."

Why, after centuries of strict secrecy, have the olohe decided to take lua public now? "Sharing the knowledge is the only way we can keep this art form alive," Paglinawan says simply. "Lua was so close to passing away," adds Mitch Eli softly. "Kenn was the last guy, and it fell on our shoulders to carry on."

Eli says the olohe feel beholden "to pass on what we know, because many people have heard of lua, but few really understand it. The book establishes a foundation, so that people can't come out and start making things up."

|

|

The senior olohe themselves reflect this mix. Paglinawan, former head administrator of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, is a project manager with the Queen Emma Foundation, which supports health care for Hawaiian communities. Kalauokalani works at Hawaiian Electric. Mitchell and Dennis Eli are both chiropractors, and Jerry Walker is a retired hospital administrator.

In 1995, the five teachers decided to split into two separate pa. Paglinawan and Kalauokalani retain leadership of Pa Kui-a-Lua, while the Eli brothers and Walker formed Pa Kui-a-Holo. Neither school charges training fees, viewing themselves as educational, not commercial, ventures.

Each lua pa trains twice a week at Kekuhaupio Gym on the campus of Kamehameha Schools. Aptly, the gym is named after the legendary lua master who taught the arts of warfare and strategy to Kamehameha. (A lua adept in his own right, Kamehameha was reputedly able to dodge or catch a dozen spears hurled at him simultaneously.)

Among the lua students are a number of women, just as stories tell of female lua warriors in Kamehameha's day and before. One of the modern-day women warriors is veteran hula dancer, former Miss Hawaii and Hawaiian Airlines community-relations executive Debbie Nakanelua-Richards.

Nakanelua-Richards admits that she was reluctant to attend her first lua class in 1992. "My brother made me go," she says frankly. "I always saw myself as a passive individual; I hate confrontation. I was fearful, thinking, hey, this is extreme!' But he said we had a responsibility to learn as much as we could about our culture, so I should get over my fear of people throwing spears at me."

As it turned out, learning lua "was like coming home," Nakanelua-Richards says. "I've danced hula all my life, so it's like muscle memory for me. I'll go through motions of strikes and holds, and it feels so natural. In hula, we use wrist movements that are similar to how one would wrestle or grab. I'd never touched a spear before, but in my hand it felt like a puili (split bamboo rattle) that I would dance with."The similarities are not surprising, since lua and hula were originally closely related in traditional Hawaiian society. During the day, warriors practiced haka, or fighting postures, in a sacred dance reserved for the temples of Ku. According to Mitch Eli, these ai were later known as "haa," then "hula." Eli says hula allowed warriors to practice their technique without giving away battle tactics. "Lua is the mother of hula," he says. "It was martial practice disguised as dance, an integral part of lua training to develop balance, leg strength, stamina and grace."

| |

As with any other martial art, Paglinawan says, many come to learn lua, but few go the distance to excel. Students "drawn by fantasies of flying in the tops of bamboo" eventually leave, he says. As lua haumana (students), those who remain learn techniques of hakihaki (bone-breaking), kuikui (punching), hakoko (wrestling) and aalolo (nerve pressure to cause paralysis).

The haumana practice techniques of "psyching out" opponents before battle with ritual insults and threatening body gestures. Mitch Eli explains: "You call on your ancestors to support you. Then, with them lined up behind you, you tell the other guy how good you are and what you're going to do to him."

Students also learn to wield and construct their own traditional weapons of wood, stone, shark tooth and bone. One recently graduated olohe with Pa Kui-a-Lua, Umi Kai, has become particularly well-known for the quality and terrifying beauty of his weapons. A car-rental company manager by day, Kai was an accomplished stone and wood carver even before he began practicing lua. He says he first attended a class out of curiosity, then stayed because the ancient discipline "filled a void I didn't know was there." Kai's finely crafted weapons have frequently been sought by art exhibitors and private collectors, but he stresses that "they're not decorative. They're made for function, not beauty."

And the function of lua weapons is to trip, rip, smash or poke: Among the ancient tools of battle are the kaane (strangling cord), maa and pohaku (sling and stone), pololu (long spear), kookoo (staff), leiomano (shark tooth club), single- and double-edged pahoa (wood daggers), and a variety of blunt hand clubs.

At a recent Pa Kui-a-Holo practice, the haumana pause after each sequence of moves to snap their feet together and, with eyes downcast, touch their foreheads to clasped hands. Mitch Eli explains that they are "paying respect to our aumakua (ancestral gods), which protect and inspire us, and help us to build the mana that's needed to do martial arts and be a better person in life."

To Western thinking, the idea that a practice meant to cripple and kill could develop good character might seem strange. But not to the Hawaiian mind, Walker says, which is aligned with lua's paradoxical wisdom.

| |

For Walker, lua has been a journey of self-discovery. "First, I saw it as a martial art," he says. "Second, as an art. Finally, and how I relate to it now, is as a way of life."

Last year, the two schools held uniki, or graduation ceremonies, for the first time, elevating a total of nine veteran students to the rank of olohe. One of Pa Kui-a-Holo's graduates was Billy Richards, Debbie Nakanelua-Richards' husband. A former Marine and Vietnam vet, Richards traces his path to lua back to his early days as a crewmember and then captain of the Hawaiian voyaging canoe Hokulea.

Wherever the canoe landed in Polynesia, Richards recalls, local warriors would greet them ceremonially. "In New Zealand, 300 came out and did haka," he says. "But we couldn't respond as warriors because we didn't know how, so we would send hula dancers out instead. And they would always ask, Where are your men?'" So in 1994, when Richards read about a lua class, he was "ready and jazzed," he says. "It was like finding that missing piece of the puzzle."| |

"Becoming an olohe completes a circle for me," Richards says today. He notes that in 1995, when voyaging canoes sailed to Hawaii from the Marquesas and Cook Islands, lua pa members were finally able to come out and greet them with haka challenges of their own.

"To me, lua is about Hawaiians discovering their warrior selves," he says. "That doesn't mean you are aching for a fight, or to beat people up. To me, being a warrior means being responsible for your conduct, and protecting your family, the people around you, your aina (land). You learn an art that can do devastating damage, but you also learn how to give and be gentle, to be responsible with that power."

.jpg)

.jpg)